William Felton, having lost his leg in an accident in 1823, decided to start a school. The school began in the front room of a house in High Street (now demolished) next to the Royal Hotel. He went to Birmingham to learn Dr. Bell’s system of education, and returned six weeks later fully qualified. The school was so successful that it outgrew the front room and moved to the old Moot Hall.

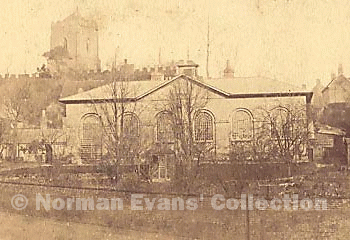

The Corporation School in Mill Street was built in 1826, and Felton successfully applied for the post of head teacher. When he retired in 1859 he was presented with a chair by grateful former pupils. Richard Holbeche could just remember him at church services in the 1850s “There sat the Blue-Coat boys in tiers. A blue curtain separated us from them, and it was quite pleasant to hear the knocks that one-legged Mr. Felton administered to their heads”.

Elsewhere in his Diary Holbeche describes the celebrations when a new Warden of the town was installed every November - boys and girls hurrying to the Blue Coat Schools “the former appearing a little later in brand new blue jackets with silver buttons and corduroy trousers. They also had woollen caps with a tuft at the top. The girls also had new clothes and neat straw bonnets ribboned with blue.”

The Corporation Schools were founded in 1826, with an annual allowance for clothing of £2.00.00 per boy and £1.11s 6d per girl. The boys had a blue cloth jacket and trousers with a shirt, stockings, woollen cap and shoes; girls had a blue cotton frock, straw bonnet with blue ribbon, shoes and stockings and a cloak. In 1834 the sum allowed for clothing was £429, and on September 1st the Education Committee ordered that “all the children be measured for their shoes and the boys measured for their clothes”. Payments were made to various shoemakers - Pimlott, Wilkins, Lucas, Rose, Gates, Ashford and Pratt, while Mrs. Smith received £12.10s.0 for bonnets and Mrs. Brentnall had £5 for knitting caps. A Committee Minute of 1836 reads “That Mr. Hacket be requested to take the trouble of ordering 400 yards of blue cloth for the boys’ clothes.”

Upper-class Suttonians tended to agree with a later comment by the Rector that the mass of the inhabitants sent their children to school not for the free education, but for the free set of clothes.