Bishop Vesey intended that his native town of Sutton Coldfield should thrive. On his travels throughout England, he saw that the cloth trade was the most profitable industry in the 1520s, and accordingly he set about establishing weaving in Sutton.

England’s chief export had for centuries been wool, but by 1500 woollen cloth was being exported rather than raw wool - rolls of broadcloth and kerseys. It was kersey-knitting that Vesey introduced to Sutton Coldfield, a kersey being a piece of cloth about a metre wide and sixteen metres long. Making kerseys was labour-intensive, it could take as many as fifteen people working for a whole week to make one kersey.

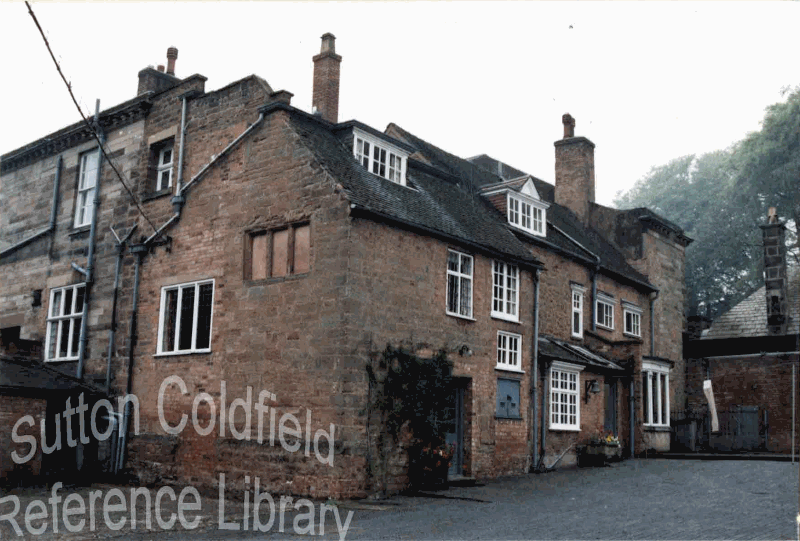

Another of Bishop Vesey’s projects to encourage the town to flourish was the building of fifty-one stone houses. Some of these houses had windows that were, for the time, quite large, letting in enough light to enable kersey-knitters to work in the room inside. He then imported a team of skilled weavers from the village of Honeybourne (near Evesham in Worcestershire) to come and make kerseys in Sutton.

There were thousands of sheep on the commons in and around Sutton producing wool in abundance, well-equipped workshops, and a good supply of skilled workers, but still the kersey trade failed to take root. Later historians thought the scheme was ill-fated because the Bishop was guilty of impoverishing his Exeter diocese in order to enrich Sutton, or because he was a favourite of Queen Mary Tudor (“Bloody Mary”), but by the time Sutton was ready to go into production in the 1530s the cloth trade was in decline; perhaps a few kerseys were woven here, but not enough to make a living.

The Honeybourne folk who had come to live in Sutton had to find other ways to earn their bread. In the seventeenth century the Parish Register records the death of John Honeybourne the little shoemaker of Reddicap, while other Honeybournes prospered - the Warden of Sutton Coldfield in 1720 and 1721 was Thomas Hunnyborne.