My family moved into accommodation, in what I am almost certain was The Camp as featured in the article, in around 1950, when I was about two, and lived there until 1953, when we were rehoused by the Council in brand new housing on Falcon Lodge Estate. Clearly at such a young age my recollections are hazy, but I do have some very specific memories, and can also recall things recounted by my mother.

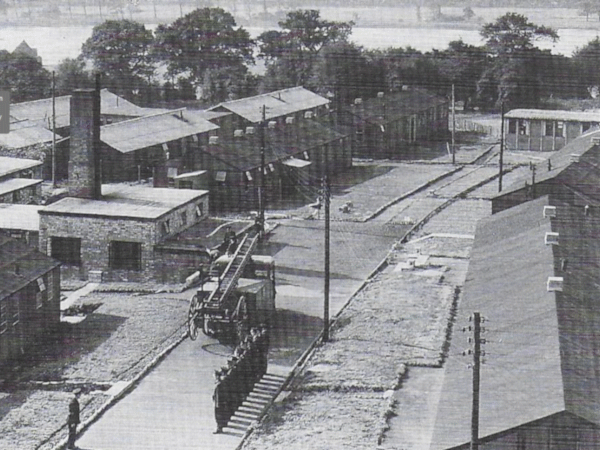

I know there was a water tower at the end of the row where we lived (our address was No. 28, The Camp), because I can vividly recall a group of residents gathering around it while one of the dads climbed up the fixed ladder to check how much water was in the tank (Could there have been a drought?). The caption to the photograph on Page 1 of Roy Billingham’s article, which shows a view of the NFS Training Camp, says that it was taken from the water tower. My memory is that the structures on the left in the photograph were no longer there during our time, but it could be that the two long buildings on the right would have included our accommodation. By coincidence I have been sent a photograph from a childhood friend and neighbour in the Camp, of him with a couple of other children outside their ‘house’ with the water tower clearly seen in the background.

My mother used to say that the huts in which we lived had been a Fire Brigade training facility, confirmed by Roy Billingham’s article, and were the officers’ accommodation. Each had two bedrooms, a living room, bathroom and kitchen, but only cold water piped in. My childhood friend’s family had the only television on the camp, and at five o’clock every afternoon his mother would lay rows of cushions on the floor and half the children on the camp would gather to watch Muffin the Mule or Andy Pandy on a flickering ten-inch screen. We had moved to Falcon Lodge by 1957 when the Jamboree took place, but my mother had been a Girl Guide and Akela to the Wolf Cubs, so we went every day.

As already noted, there was only a cold-water supply. If hot water was required either a kettle on the electric stove or a pan on the coal fire would provide. One day I was pottering outside in the little garden with my bucket and spade. While I was pottering, my mother decided to take a bath, which involved spending quite some time heating kettles and pans of water over and over again until enough hot water had been accumulated in the bath. Having judged that there was enough in the tub she’d gone into the bedroom to get undressed. As I’d filled my bucket with earth, for some reason I took it inside and, in the bathroom, saw the tub half full of clear, clean hot water. Although I can picture the scene even now, I have no idea of what made me do it, but the bucket was emptied into the water, and I went out to the garden for a refill. I was busy in this task when I heard my mother’s howl of horror from inside. I think she did eventually forgive me.

Living surrounded by woods was a perfect environment for children in which to have endless adventures, and whether Robin Hood or Roy Rogers, these often involved horseback chases. A handy prop for these games was a domestic broom: standing astride the handle, the brush head became the horse’s mane, and with a ‘gee-up’ we would gallop off into the surrounding woods. One day I came home on foot. ‘Where’s my broom?’ my mother asked. I realised I’d left my horse tethered up in the woods, and although my mother and I formed a posse to search for it, it was never found. As an adult living in the area, if I ever was in the park near those woods, I would find myself still keeping an eye open for that broom.

There was a Polish family in the camp, but the grandmother only knew one word of English: ‘sixpence’. She would sometimes ask one of us children to run an errand for her, and somehow with much miming and ‘sixpences’ we usually got the message.

My grandfather was a steam engine driver, and whenever they came to us on holiday it was mandatory to ride on the miniature railway that ran from near Town Gate.